Black Women In Art: A Right To Be Seen

by Hannah Marsh

The Zanzibar-born British artist Lubaina Himid (b.1954) made a historical mark on the British art canon in 2017 by becoming the first Black woman to win the Turner prize, acknowledging her ground-breaking practice of channelling the intrinsic value of Black lives.

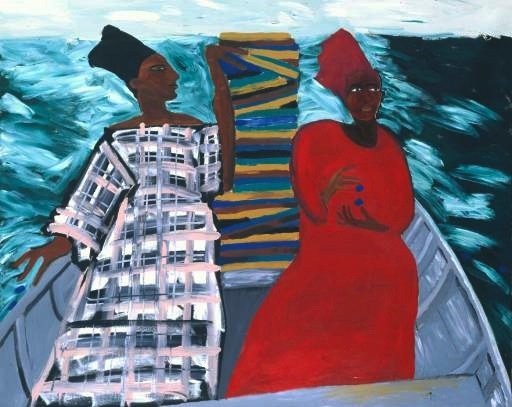

In her work, Himid celebrates the resilience and brilliance of Black women as a means of challenging and taking revenge on the European canon of art that has consistently depicted Black women in problematic ways. The piece between the two my heart is balanced is exemplary of Himid’s challenge upon the canon. The importance this artistic resistance has for the contemporary position of Black women, as well as its influence on my own body of work, will be discussed in this post.

Such revenge can be understood in the work between the two my heart is balanced, (Fig 1) which depicts two Black women placed inside a leisure sailing boat, dressed in bright garments and holding what appear to be maps- the women are embarking on an adventure. Both the title and content of Himid’s painting reference and re-work an etching by European master Tissot titled Portsmouth Dockyard, (Fig 2). Portsmouth Dockyard depicts a man dressed in traditional military attire, sitting beside a woman dressed in a frock with an umbrella. The two appear to be enjoying a leisurely, bourgeois lifestyle. However, the soldier’s attire and the striking navy flags in the background of Tissot’s painting remind us that such a lifestyle has been facilitated by British colonial conquest. The Black women in Himid’s recreation of the scene replace the soldier and the women, dramatically occupying the very spaces symbolic of their social oppression in Tissot’s scene. Himid’s recreation banishes Tissots’ original characters, mirroring the relegation of Black women within the canon. The women powerfully occupy the space society at the time of Tissot’s painting would have expelled them from. They do so with maps in hand, declaring themselves scholars and explorers reclaiming their rightful space in art history as independent, philosophical, autonomous beings. This is noted by Griselda Pollock in Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writings of Art’s Histories as she suggests that the women in Himid’s series are ‘philosophers, theorists, revolutionaries’ and not ‘exhibited booty’, as so typically apparent in the canon.[1]

Himid thus challenges the spaces Black women have occupied in art history, by reclaiming a space symbolic of power and adventure in Tissot’s original scene. Black women in Himid’s recreation are no longer relegated to a position of service, or sexual objectification. This is metaphorical of the driving force Himid offers to Black women in contemporary art, helping to create a space for Black women to creatively excel in.

It is this reclaiming of certain social rights historically denied to Black women, and the visibility she has given Black women that inspired my body of work entitled, for Eya, Susie and I. The work consists of drawing, performance, photography and sound, seeking to make commentary on institutional racism, and the spaces Black women occupy within institutions. The work was displayed in Squeeze (the University of Leeds fine art degree show), Leeds Left Bank Art Prize and the FUAM art prize.

Informed by art history, I was critically aware of my surroundings- a school resource rich and ready to academically discussing race but lacking in racial diversity among its student and teaching body. I felt uncomfortable writing about race in relation to art from a distance, when the lack of diversity within the school was a clear indicator of a wider social issue. I had been researching my family history, recording my grandmother, Eya Couloute’s experiences of racism when moving to the U.K from Saint Lucia in the 1950’s. She significantly recalled working as a cleaner at Rugby train station for the majority of her adult life, in which she was subjected daily to racism, an aspect of work she simply had to endure to sustain a family of nine children. It became difficult to separate my own context from my grandmother’s. Racism has improved since the 1950s in Britain, nonetheless, a black migrant of Ghanaian heritage was one of few Black people within the entire fine art school. The spaces Black women occupied in society during the 1950s and the spaces we occupy now, I felt, had not changed.

As a result, my work became concerned with the spaces Black women occupy within institutions. I thought about the space I occupied within the school, simultaneously a part of it and outside of it on a wider social scale. I spent some time with the school’s cleaner Susie, shadowing her shifts. Susie allowed me to record her for artistic purposes, specifically recounting her own experiences cleaning in the Fine Art school. She recalled her daily tasks and techniques but also openly shared how she is often ignored despite seeing the same faces every day.

Much to my surprise she acknowledged that certain attitudes toward her may be due to the colour of her skin, concluding my recording by stating, ‘some people are very bad to black people, you know this’. The two narratives, whilst speaking from contexts separated by 50 years, held a painful similarity in their experiences of Black woman working in Britain. Very much inspired by Himid’s work, I too wanted to rework the notion of the invisibility of Black women within the art world and society in general. I wanted to make Black women visible within my work and reclaim the spaces they have been unable to occupy through the labour of cleaning- a process consistently performed by both Eya and Susie, but never seen.

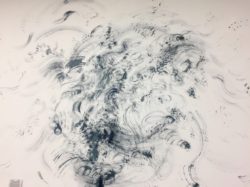

To make this process visible, ink was applied to cleaning tools and marks were made upon the walls (Fig 3) and upon the floor of the Fine Art school using acrylic paint. This was intended to make the gestures of both Susie and Eya visible, drawing attention to racism apparent during Eya’s working life and still present in Susie’s. The piece also included a performance during the opening night of the Fine Art degree show (Fig 6). Well aware of how lacking in diversity the night would be, I curated a performance that consisted of three other Black students from the University of Leeds and myself cleaning different floors of the degree show. Moving around people as though completing a cleaning shift, we feigned ignorance of our surroundings and our audience. The piece seemed successful in making people feel uncomfortable and I hope it was eye-opening to viewers in relation to what my work was attempting to convey.

The photographs within the body of work consisted of an image of my grandmother’s living room, (Fig 4) recognising Eya’s creativity: making the interior of her home a safe and special space that defended her against a 1950s Britain where she was barred from accessing the luxuries of public spaces. This photograph was placed inside a gold frame and hidden on the window ledge behind a plant pot in the degree show, alluding to the notion of the invisible Black woman. Photographs accompanying the work were also hidden under the steps of the Fine Art building, one in particular depicting the sharp and harsh structure of Rugby’s railway station (Fig 5) to contrast the warmth within the Caribbean 1950s home. The sound piece from the work featured Eya and Susie reflecting on their encounters with racism as cleaners, with my own voice mid way reflecting upon my own position with the art world as a black artist. This played from inside Susie’s cleaning cupboard, a hidden installation that was once againsuggestive of the unheard and hidden difficulties black woman face.

The body of work seeks to spark discussions surrounding race, adding to the discourse within contemporary art regarding representations of Black woman. Just as Himid’s work offers a sense of empowerment to Black woman and demands the rights they have been repeatedly denied throughout history, I too hope that my work will help to make society cognizant about its race-related flaws in order to move towards a racially diverse and equal future.

[1] Griselda, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writings of Art’s Histories, (Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group) p.182.