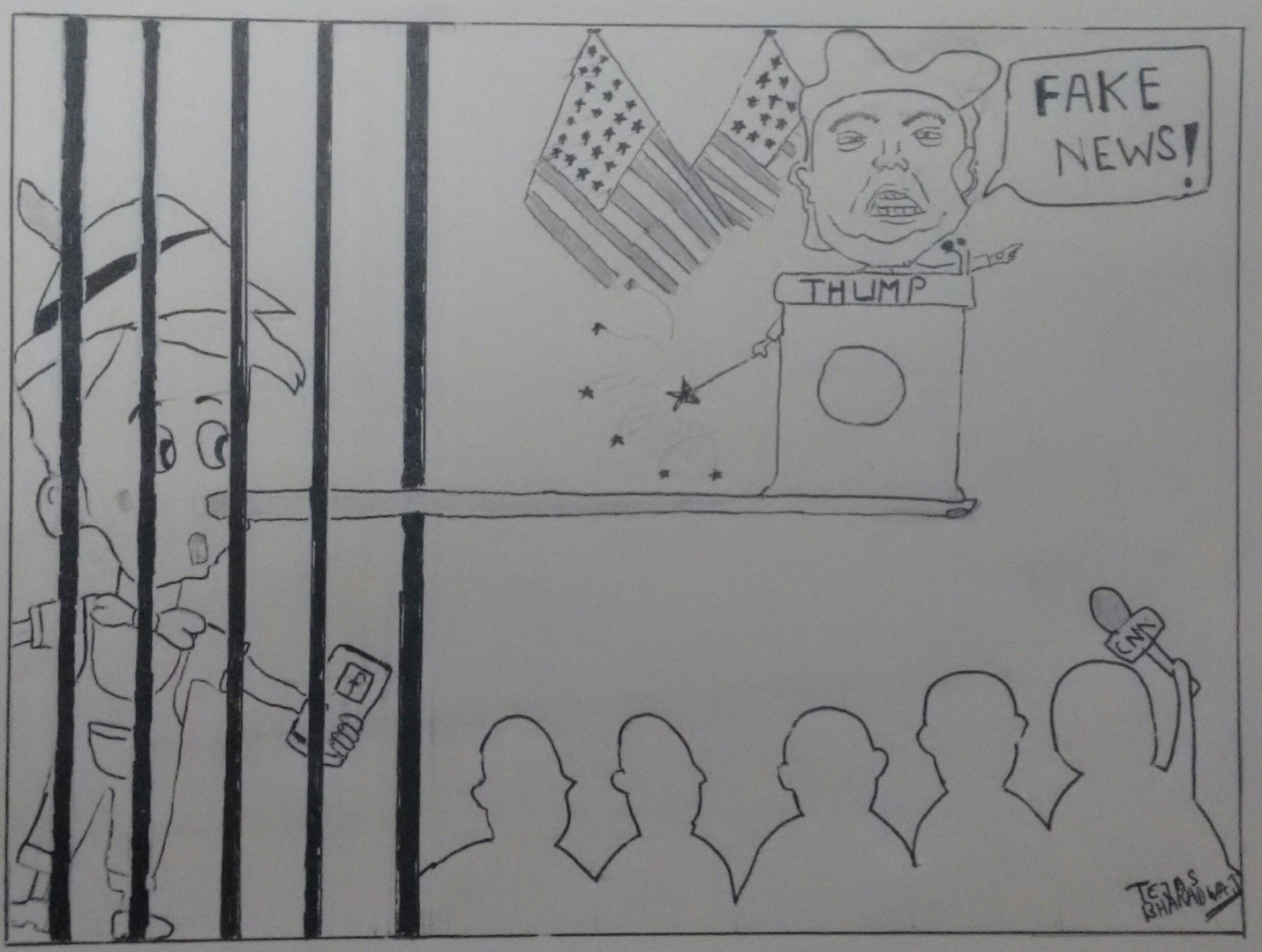

How Much Can You “Fake it” 'Til You “Make it”?

by Tejas Bharadwaj

Neo-Journalism encompassing inter alia fringe medium such as Individual Online Bloggers have profoundly thrived on strong Regional and International Legal Standards[1] to offer them protection from arbitrary restraints on free speech. Thus in pursuit of an authoritative Nostrum towards countering fake news online and incongruently fostering a postulation of realist impartation by individuals for the popular benefits, this research is sculpted within the framework of the International Law. As aforementioned it is imperative to deplore the publication of fake news online through a strong deterrent mechanism. States, by promulgating Legislations to counter fake news[2], are often left contemplated by the International Human Rights framework’s[3] tripartite test[4] that examines every Legislative restriction on free speech. The test of i) Legality[5] ii) Legitimate aim[6] and iii) Necessity[7], challenges the State in establishing the reasonability of the restriction imposed on any claim of free speech violation at international or regional human rights courts. While it is appreciable for States to restrict any expression pursuant to protection of public order, national security and even the rights and reputations of others[8], it becomes incompatible when states apply fake news as a blanket term to penalize other legitimate forms of expression such as criticisms on public officials, satires and value judgments, which stifles the foreseeability of the online bloggers to possibly understand those forms of expressions that are punishable. With grey clouds looming over the application of fake news laws creating a chilling effect on bloggers, states have also gone extra-legal by looking up to the social media platforms for a catharsis.

YouTube, Twitter, Google and emphatically Facebook have been mongers of fake news notably in instances such as the 2016 US Presidential Election and Brexit Referendum. Statisticians believe that Facebook in particular has facilitated rapid spread of fake news owing to its global usage, patronage and algorithms easing distribution of information[9]. Facebook’s news feed during the election campaign promoted stories like “Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump’s Presidential Candidacy”, “FBI agent suspected in Hilary email leaks found dead in apparent murder suicide” which are indicative of strong partisanship and pro-Trump allegiances, with critics adducing these as influential factors of the Presidential election results[10]. Facing heat, Zuckerberg resorted to denying Facebook as a media company and claimed it as a Tech company[11]. Further, its Chief Operating Officer substantiated by saying “At our heart we're a tech company; we hire engineers. We don’t hire reporters, no one’s a journalist, and we don’t cover the news”[12].Arguendo, ignoring the tech company debate, online intermediaries such as Facebook ascribe as “mere conduit” and are protected from liability arising from third party content posted when they have not selected the receiver of the transmission, modified the information or expeditiously removed the content knowing its illegality or after notice by government, as per United Nations & Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe[13]Council of Europe[14] and Court Decisions.[15] Moreover, such platforms aren’t obliged to monitor posts in their platform. Consequently, the original authors of such posts are spotlighted. Under the dynamic technological proliferation that modern global media sustains, it becomes far-fetched to limitedly interpret journalism[16]. This ushers to the issue: are bloggers journalists and are they afforded similar legal safeguards while posting fake news?

Decisively, bloggers are categorized as journalists[17], including citizen journalists who momentarily carry out such functions through social media[18]. The ECtHR[19] held social media as a vital source of political information and has provided impetus to citizen journalism that assists in constructing public discourse and disseminating information uncovered by traditional media.

Agonizingly, despite such importance, the social media bloggers are often left vacillating about the kinds of expressions that are illegal under international human rights law, especially when posting fake news.

The State is refrained from prohibiting discussions or dissemination of information received, even if it is strongly suspected that such information might not be truthful[20]. Moreover limiting the dissemination to only true or state-sanctioned news poses a threat to democracy itself. It is also common for journalists to make factual errors as they do not have the time to wait until they are sure that every fact alleged is true before they publish a story. ECtHR[21] held, “News is a perishable commodity and to delay its publication, even for a short period, may well deprive it of all value and interest.”

Distortion of reality such as exaggeration[22] and satirical elements[23] employed by journalists are also the possible recourses available under the law, aimed to attract readers' attentions, provoke them and increase the awareness on issues especially in the context of the public debate of affairs[24]. This encompasses the use of the deceptive “Click baits” by online bloggers to attract readers[25].

Mindful of the safeguards meted, the bloggers also must possess acumen that freedom of expression is not absolute and the State is absolutely entitled to restrict those expressions that incite hate, racism and xenophobia[26]; are obscene[27]; agitate violence; compromise security and public order[28]; and baselessly violate the rights and reputations of others[29].

Expressing the possibilities for algorithmic reforms by social media and state actor’s commitments to refrain from general prohibitions on the dissemination of information based on vague and blanket terms such as fake news[30], I would like to conclude by stating that “a world devoid of lies holds no truth”.

[1] Article 19 & 20 ,International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (adopted 16 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976) 999 UNTS 171; Article 13, American Convention on Human Rights(adopted 22 November 1969, entered into force 18 July 1978) ; Article 9, African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (adopted 27 June 1981, entered into force 21 October 1986) 21 ILM 58 hereafter; Article 10 European Convention on Human Rights (adopted 4 November 1950, entered into force 3 September 1953) 213 UNTS 1932; Article 11, The Charter of Fundamental Rights of European Union (entered into force 1 December 2009) 20 2012/C 326/02; Article 32, Arab Charter on Human Rights(adopted 22 May 2004, entered into force 15 March 2008)

[2] France tables “fake news’ Law EU Observer (5th February 2018) available at <https://euobserver.com/tickers/140838> [accessed 9th February 2018]

[3] Ibid

[4] UNHRC General Comment 34‟ (12 September 2011) UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34 para 22; The Sunday Times v. United Kingdom App no 6538/74 (ECtHR, 26 April 1979) para. 45

[5] Korneenko v. Belarus, Comm no 1226/2003 (UNHRC) para 10.7; The Johannesburg Principles On National Security, Freedom Of Expression And Access To Information para 1.1

[6] Lohé Issa Konaté v The Republic of Burkina Faso (December 5, 2014) (African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights); CM/Rec/2014 Council of Europe , Guide to human rights for internet users, para 5.2; UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression (11 May 2016) para 7.

[7] Ross v. Canada Comm No. 736/1997 (UNHRC, 17 July 2006); Ballantyne, Davidson, McIntyre v. Canada Comm No. 359/1989 and 385/1989. (UNHRC, 31 March 1993)

[8] Article 19 (2) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

[9] Juju Chang, Jake Lefferman, Claire Pedersen and Geoff Martz, “When Fake news Stories Make Real News Headlines,” ABC News, Nov. 29, 2016, (“Facebook is the platform where this stuff is taking off and going viral,” said BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman, who has studied the spread of fake news) available at <http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/ fake-news-stories-make-real-news-headlines/story?id=43845383> [accessed 13th January 2018]; Fresh Air “Fake news Expert On How False Stories Spread And Why People Believe Them,” NPR, Dec. 14, 2016, (Dave Davies interviews Craig Silverman of BuzzFeed News), available at <http://www.npr.org/2016/12/14/505547295/fake-news-expert-on-how-false-stories-spread-and-why-people-believe-them> [accessed 12th January 2018]

[10] FAKING NEWS, Fraudulent News and the Fight for Truth, PEN America (October 12 2017)

[11] Facebook won’t call itself a media company. Is it time to reimagine journalism for the digital age?

The Verge (16th November 2016) available at: <https://www.theverge.com/2016/11/16/13655102/facebook-journalism-ethics-media-company-algorithm-tax> [accessed 15th January 2018]; Facebook CEO says group will not become media company. Reuters (29 August 2016) available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-facebook-zuckerberg/facebook-ceo-says-group-will-not-become-a-media-company-idUSKCN1141WN> [accessed 15th January 2018]; Mitch Joel, Facebook Is Not A Media Company (Today). Facebook Is The Mass Media (Tomorrow)., Medium (2 February 2017) available at: <https://medium.com/@mitchjoel/facebook-is-not-a-media-company-today-facebook-is-the-mass-media-tomorrow-b4c0a26da9a3> [accessed 15th January 2018]

[12] MEMO TO FACEBOOK: HOW TO TELL IF YOU’RE A MEDIA COMPANY, Wired (10 December 2017) available at: <https://www.wired.com/story/memo-to-facebook-how-to-tell-if-youre-a-media-company/> [accessed 17th January 2018];

[13] Joint Declaration by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and the OAS Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression (21 December 2005)

[14] Council of Europe, ELECTRONIC COMMERCE DIRECTIVE, DIRECTIVE 2000/31/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL Article 12-15. (2000); The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, Declaration on freedom of communication on the Internet, Principle 6 (28 May 2003)

[15] Tamiz v. The United Kingdom App no 3877/14 (ECtHR 19 September 2017) ; Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, W.P. (Crim.) No 167 of 2012 (Supreme Court of India 24 March 2015); R.M.B c/Google y ot. s/ Ds y Ps, Fallo R.522.XLIX, (Supreme Court of Argentina 29 October 2014)

[16] Lee v. Dept. of Justice, 401 F. Supp 2d 123 (D.D.C, 2005) (USA)

[17] Ibid (n.6) UNHRC General Comment no 34; Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe (2000) Recommendation no 7

[18] Frank La Rue, United Nations General Assembly, Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right of freedom of opinion and expression A/HRC/20/17 (4th June 2012) para 4

[19] Cengiz and Others v. Turkey App No 48266/10 and 14027/11 (ECtHR 1 Dec 2015)

[20] Salov v. Ukraine App no 65518/01 (ECtHR 6th September 2005) para 113

[21] Sunday Times v. United Kingdom (No.2) App No 13166/87 (ECtHR 24th October 1991) para 51

[22] Thoma v. Luxembourg App no. 38432/97 (ECtHR 2001) para 43-45; Gaweda v. Poland App no. 26229/95 (ECtHR 14 March 2002) para 34; Prager and Oberschlick v. Austria 21 E.H.R.R (1996) para 39

[23] Vereinigung Bildender Kunstler v Austria 47 EHRR (2008)

[24] Nilsen & Johsen v. Norway para 52

[25] Naima Bouteldja, Journalism in the era of Click Bait, Al Jazeera (13 April 2017) available at <http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/04/journalism-era-clickbait-170413091027734.html.>[accessed 21 January 2018]

[26] Article 20 ICCPR; see also JRT and the WG Party v. Canada, Comm no.104/81 (UNHRC)

[27] Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476 (1957); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942)

[28]Article 19(3) ICCPR; Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’ (1985) 7 HRQ 3, 6; Concluding Observations on the United Kingdom (2008) UN doc CCPR/C/GBR/CO/6, para 26.

[29] Ibid Article 19(3); See also Castells v. Spain, App No. 11798/85, (ECtHR 23 April 1992)

[30] Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and “Fake News”, Disinformation and Propaganda (3rd March 2017)