The Politics of Language and the Marginality of the Amazigh of Morocco

by Sara Green

To think about language as anything other than a simple and neutral mode of communication – especially in the Anglophone world, where the assumed universality of the English language offers little opportunity for self-reflection – seems like somewhat of a non-issue on the surface. However, thinkers such as Ngugi Wa Thiong’o have emphasised the role of a language as a ‘carrier of culture’; how in its very make-up, it reflects a collective memory bank, a shared experience, and a particular perception of the world formulated by this history. In this view, the marginality of the indigenous Tamazight languages in Morocco, rather than reflecting a ‘neutral’ pragmatic preference for one lingua-franca such as Moroccan Arabic, instead reflects a historically-rooted marginalisation of Berber cultures in relation to how Morocco foments its mainstream cultural narrative.

But exactly how historically-rooted is this marginalisation?

Morocco’s history under the French and Spanish Protectorates (1912-1956) suggests quite the contrary; that in spite of Colonial efforts to naturalise and emphasise cultural and linguistic differences between ‘Arab’ ‘Jewish’ and ‘Berber’ essences, broad collaboration and inclusivity within the ranks of Moroccan nationalists rejected these efforts outright. Indeed, looking at the dialects spoken themselves can reveal how fluid these markers of ‘Arab’, ‘Jew’ and ‘Berber’ really are; many Jewish communities spoke a ‘judeo-Arabic’ dialect, and Moroccan Arabic is so heavily drawn from the grammar and phonetics of Berber languages that its differences from Classical Arabic is evident even to me as a fairly new student to both. Furthermore, Moroccan actors in anti-colonial resistance knew that these colonial ethnic distinctions were arbitrary attempts at divide-and-rule; in response, a diverse narrative of Moroccan identity was formulated, of the historical acceptance of and coexistence with Jewish refugees, and the Islamic unity between Berbers and Arabs. Whilst it may be naïve to hold this up as a ‘success’ story, it is striking how these attempted ethnic distinctions were seen for what they really were; as in other contexts, for example the French reinforcement of Sectarian difference in Lebanon, have had much deeper and devastating effects.

So how did Tamazight become so marginal?

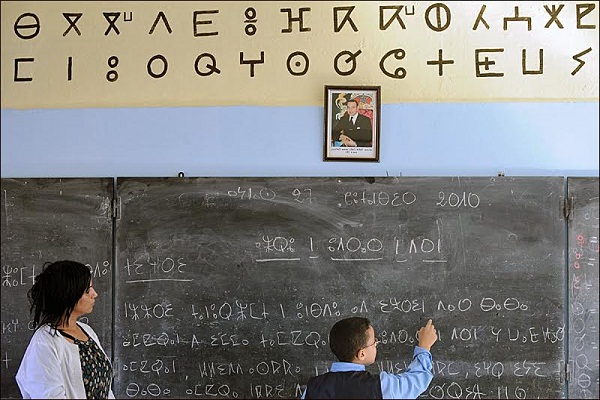

As a result of ‘Arabisation’ government policies in the following decades of Independence, Tamazight languages were slowly pushed to the margins to create a singular Arab-Islamic essence in Moroccan identity. Similarly to the case in Algeria, the creation of a young nation state will often demand a singular ethnic and linguistic identity, and seek a means of self-definition that was not allowed during Colonial rule. If the rejection of Tamazight languages in government policy represents a rejection of a cultural knowledge, it also represents a profound political marginalisation too. Whilst these measures symbolically erased Amazigh contribution to Moroccan society, its practical implications were just as significant; inability to access higher educational and employment opportunities, difficulty accessing government services, and a general alienation from media, education and mainstream cultural narratives. This alienation, beginning as a school-aged child, often cultivates a separation and eventual resentment of one's own language, thus culture, as being removed from all things cultural, political and economically beneficial.

This marginal status of Amazigh communities also manifested in the poor infrastructure and poor access to health and education that is, sadly, typical of Berber-majority mountain villages. Indeed, recent protests in the Rif region (2017, following the momentum of the February 20th Movement) reflect these concerns exactly. Whilst grassroots political activism is evidently of profound importance, it is also crucial to avoid the historical amnesia that the Arab-Islamic vision of Morocco prescribes; indeed, this same Rif region was a famous site of anti-colonial resistance, resulting in the short lived Rif Republic that revolutionaries such as Che Guevara looked to as a model. The Rif Rebellion, led by Berber tribes and more anticolonial than Pan-Islamist in its intentions, cannot fall under an Arab-Islamic understanding of Moroccan society; nonetheless it is a profoundly important chapter of both Moroccan and Anticolonial histories in general. The work of historians like Jonathan Wyrtzen contributes greatly to this, in the hope that historical inclusiveness will allow ‘Berber’ identity to exist both distinctly and as a valued part of the mainstream cultural narrative; in the hope that Tamazight language and culture can be engaged with and appreciated as nothing less ‘rich’ and ‘cultured’ than Arabic.