Féminicides in France: ‘On me prendra au sérieux quand je serai morte’

by Olivia McGhie

‘On me prendra au sérieux quand je serai morte’ - 'They’ll take me seriously when I’m dead'

The streets and grand boulevards of Paris, rich with culture and romance, enmeshed and entwined with the stories and love affairs of great writers and philosophers have been plastered with slogans calling for an end to “féminicides”. “Féminicides” is the French term for the gendered murder of women by their partner or ex-partner. Since the 1st of January of this year, 130 women have been murdered by their boyfriend, ex-boyfriend, or father in what feminist groups are calling a state of emergency. These statistics put France, second only to Germany, as the country with the highest rate of domestic violence resulting in the death of a woman in Europe.

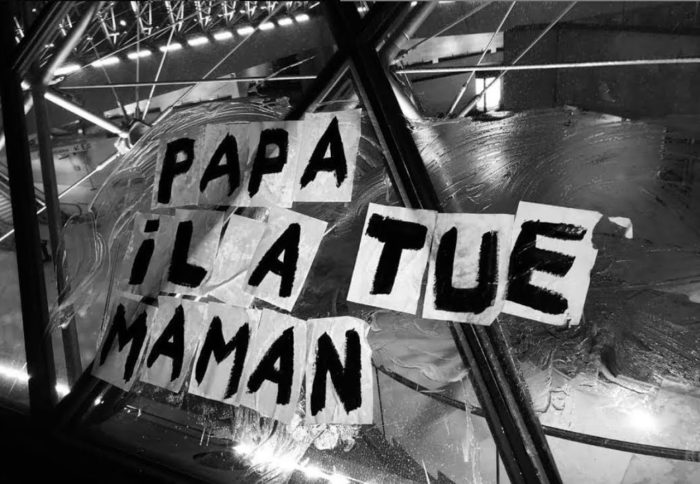

The slogans are plain and simple: a few black words against a white backdrop. “Papa il a tué maman” (Daddy killed mummy) or “Elle le quitte. Il la tue” (She left him. He killed her). The phrases are brutal, honest, and direct. They are intended to wake France up from the indifference these feminist activists say the French state has towards these murdered women. They accuse the government, courts, and police of all being complicit in the murder of these women in failing to take their cries for help seriously. In 2018, a third of all victims of femicide reported their harassment to the police but still went on to be killed by the same men.

After calls from feminists for Macron to “wake up” over the summer, the French government has pledged to spend more on anti-domestic violence initiatives. In September the Prime Minister Edouard Phillipe promised €5 million to build an extra one thousand shelters for women fleeing domestic violence and an extra €1 million for more general measures to help victims of domestic abuse. The Prime Minister said whilst announcing these initiatives that, “for centuries, women have been buried under our indifference, denial, carelessness, and old-machismo and incapacity to look this horror in the face”. However, organisations involved in the anti-femicide campaigns have accused the French government of presenting a façade in dealing with the problem arguing that billions of euros rather than millions are needed to resolve this huge issue that plagues France.

The stories of these women from all over France, of all ages and races make for a bleak reading. Too often they are ignored by the police and courts. In fact, it was when President Macron was visiting a national domestic violence hotline centre to launch his governments new plan to tackle the crisis that he experienced the problem first-hand. A woman had rung the hotline after being refused a police chaperone to go with her to her house to collect some belongings after finally deciding to leave her husband who had subjected her to decades of violence and abuse. The police officer said he could not because he needed a judicial order to intervene. He was wrong but the helpline could not help the woman either, merely direct her to a support group. The words of Julie Douib, shot and killed by her ex-partner in Corsica despite filing several police complaints which explicitly says that she feared for her life, hangs over this episode like a shadow: “On me prendra au sérieux quand je serai morte” (They’ll take me seriously when I’m dead).

Her words make for an uncomfortable truth. Too often are actions taken towards tackling domestic violence after a murder of a particular woman captures the heart of a nation. Yet, the truth is that one woman in France is killed every forty-eight hours in cases of domestic violence and most of the time their stories go untold. The money that the French government has pledged to spend on domestic violence initiatives should be welcomed but must be understood as simply a remedy to the symptoms rather than the problem itself. The women who cannot leave their partners and reach a shelter, who cannot ring a hotline, or who cannot get to a police station are the forgotten victims. The problem starts before the police get involved, or before the courts intervene: the problem starts when a man thinks that he has the right to abuse a woman, emotionally, physically, or financially. The toxic masculinity that exists all over France and all over the world must be addressed in order to tackle the root cause of violence towards women. Women must not fear going to the police, but more importantly they should not fear men.

(Warning: the following paragraphs may contain emotionally sensitive information)

Here below are some of the stories of women who have been killed by their partners in France in October of 2019:

Safia, 32 years old, a mother of four children between the ages of 2 and 11. In April of this year she filed a complaint against her husband who she had separated from earlier in the year. In October, he came to her new apartment and stabbed her to death several times with a knife.

Berthe-Natacha, 38 years old, a mother of two children aged 15 and 20. A few months ago she and her boyfriend split up. In October, he ambushed her as she was getting in her car to go to work. He stabbed her in the throat and heart. She died before the emergency services arrived.

Unknown-name, 21 years old, student of arts and culture at the Sorbonne. She was in her bedroom with her boyfriend in her parent’s apartment. They heard fighting coming from upstairs. They did not see exactly what happened, but she fell from the twelfth floor and died. She had filed a complaint against her boyfriend in January. He had to complete a citizenship course but was subject to no further checks or surveillance by the police.

Study Abroad Columnist: Olivia McGhie, 3rd Year BA History Undergraduate. Currently studying abroad at University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, Paris.