Human Rights and Decolonial Thought: A Marriage of Two Contemporaries?

By Azhar Vickland

The ‘Decolonising Human Rights’ panel event was held on 22nd October 2020, by the Leeds Human Rights Journal and the Centre for Ethnicity and Racism Studies (CERS) for Black History Month. The speakers on the panel were all from the School of Sociology and Social Policy and CERS: S. Sayyid, Ipek Demir and Walaa Al Husban, with Sarah Marusek moderating the questions posed on the chat. The members of the Leeds Human Rights Journal Editorial Team (Henna Tammi, Niamh Punton, Poppy Cohen, Zahra Iqbal, Rachel Clayton and I) administrated the event. Over the last few years, there have been a number of ‘Decolonising a subject area’ panels at the University of Leeds, therefore, we saw an opportunity to extend the conversation to the discipline of human rights.

To accomplish this, there has to be a reflection on what ‘decolonising’ means, is it a mere departure of Western thought on human rights? or a re-framing of the lenses in which we view the discipline of human rights?

The three speakers on the panel were able to apply decolonial thought, to the discipline of human rights through a sociological perspective. This article sets to break down the decolonial perspective discussed by the speaks on the panel. Starting with Ipek Demir’s consideration of the contributions made by diasporas and non-Europeans via liberation movements and civil rights struggles. Next, it analyses Walaa Al Husban’s proposition of resisting the concept of universality of human rights. Lastly, it explores S. Sayyid’s decolonial telos of defining what it means to be human before serving justice to the ‘colonised other’.

Ipek Demir’s talk started with acknowledging the failure to recognise that the current world has been shaped by European countries and non-Europeans. Firstly, and integrally, there has to be a realisation of the presence of Eurocentrism in the discipline of human rights; this means that Europe is seen as a ‘miracle’ and that multiculturalism is relatively new to Europe. This realisation also shows how European nations are able to commit human rights violations, as we have seen in the refugee crisis and the presence of hard borders to maintain the ‘sanctity’ of Europe.

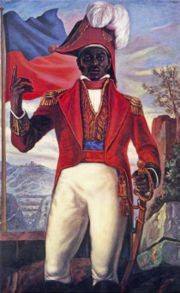

Leading on to the next part of her speech, Demir appreciated the struggles by diasporas in the field of human rights, from the Haitian Revolution, the Civil Rights Movement, the Bristol Bus Boycotts to the current Black Lives Movement (BLM) protests. Demystifying the notion that European revolutions paved the way for key milestones in human rights and that Western philosophers had the monopoly over human rights.

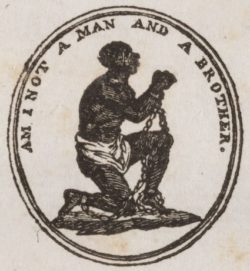

The next speaker, Walaa Al Husban, addressed the flawed project of universal human rights and the harm this has done to ethnic minorities, immigrants and refugees. Al Husban explained that this is due to the conception of the ‘sub-human other’ or the ‘colonised other’. Stemming from the device of human rights being by the colonisers, to rehabilitate the uncivilised world and take those inhabiting it as their colonial subjects. This has since persisted with international organisations from the West making decisions on behalf of lesser developed countries and communities.

This led Al Husban to talk about her personal experiences working in the Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan. Differentiating how the human rights discourse and human rights law has regulated her identity from being a victim into an active agent.

She then discussed the problem of securitisation of Islam in Western countries and the treatment of refugees living in camps or trying to cross borders; ultimately perpetrating human rights violations under the guise of national security. Al Husban calls for a decentralised approach to the interpretation of human rights, effectually making it a device to serve justice to marginalised communities and not to patronise them.

The final speaker, S. Sayyid, delivered his address by calling for us to evaluate the genealogy of human rights before we attempt to decolonise it. To undertake this task, firstly, we have to consider the current world that we live in. Colonisation and modernisation have been intertwined processes in the making of this world. Further separating humans into two categories: the western modern being and the ‘other’ colonised being. The western being takes themselves the authority over human rights and the responsibility to discipline the colonial being. This reproduces a double standard when engaging in the human rights discourse, as the laws and norms created by the ‘colonised other’ will be naturally interpreted as human rights violations. On the other hand, the laws of the modernised western being are morally and legally upright, serving them justice to the best achieve the best standard of human rights.

This follows through the liberal understanding of human rights, which Sayyid suggests, does not see itself capable of violating any human rights. In other words, liberalism has been compatible with the horrors of slavery and genocide and colonialism. Thus, decolonising human rights requires an unmooring from liberal understanding. Instead, it is necessary to adopt human rights as a pragmatic device which is applicable to various contexts as a tool for justice. This uproots human rights from its Eurocentric conceptualisation which has been entrenched in international law, grounding it contextualized definitions of justice.

Focussing on the theme of decolonial thought, all speakers had the common point of acknowledging that we do indeed live in a post-colonial world. European influences have dominated multiple spheres of academia, government and international organisations, in the field of human rights. Coming to terms with this is the starting point of decolonisation. Just as geographical decolonisation was the withdrawal of Europeans from colonised lands, intellectual decolonisation is the withdrawal of European thought from academia (our minds). This is a dynamic process, as we have seen from the different perspectives of the speakers. Demir’s approach is to focus on the contributions made by the diasporas, highlighting that the revolutions against the colonisers have to be taught in the curriculum as opposed to only teaching us about the e.g. French Revolution. Al Husban’s proposition is to reject universalism, to create an approach that is more decentralised for the non-West. Sayyid argued that decolonizing human rights means recognizing as just another way of demanding justice.

There is a deep entrenchment of Western philosophies within the human rights canon. Therefore, the foundations laid for the decolonisation will be essential for this discipline. The addresses made by the speakers hint at the initial phases of the decolonial process, which has been ongoing for the last century (very much an indication of how complex this process is). The complexities of this process reaches further than the sociological deconstruction of human rights, the political and legal branches of this field will have to be considered too.

The next HRJ panel event in collaboration with the ECR2Psoc (on Human Rights Day), seeks to explore the Responsibility to Protect and its implications beyond Europe, with academics from the ECR2P at Leeds.

Lastly, I will use this post to express my gratitude to everyone involved in the event: Dr Demir for helping me throughout the planning process and for making this event possible; Walaa; Prof. Sayyid; Dr Marusek for devoting their time to prepare and participate on the panel; the Leeds HRJ Editorial Team for working the administration of the event, from marketing all the way to sending me their notes to write this blog and the attendees who were cooperative and engaging during the event.

Azhar Vickland, Editor-in-Chief of the Leeds Human Rights Journal and Final year BA Politics and Social Policy Undergraduate.

Notes compiled by Leeds Human Rights Journal Editorial Team: Poppy Cohen, Rachel Clayton, Zahra Iqbal.